Pagan // 2008-2010

Christmas, Strechannie, Summons of the spring, Palm Sunday, Easter and Funeral rites, St.George’s Day, Whitsunday, Midsummer, the Saviour, Zazhynki, Dazhynki, Dziady. Nowadays they are called folk holidays or rites and are even depicted in schoolbooks. In the units “Belarusian legends, myths, and stories” our ancestors are described to explain all nature and life phenomenon by the existence of living creatures – spirits. House, forest, and field had their spirits. Brownie mastered the house, wood-goblin mastered the forest, and mermaids mastered the river. Lightening is an enraged God, and stars are people’s soles. People worshipped stumps and stones, sun and thunder, animals and birds, plants and ponds; these were respected, afraid of and asked for help.

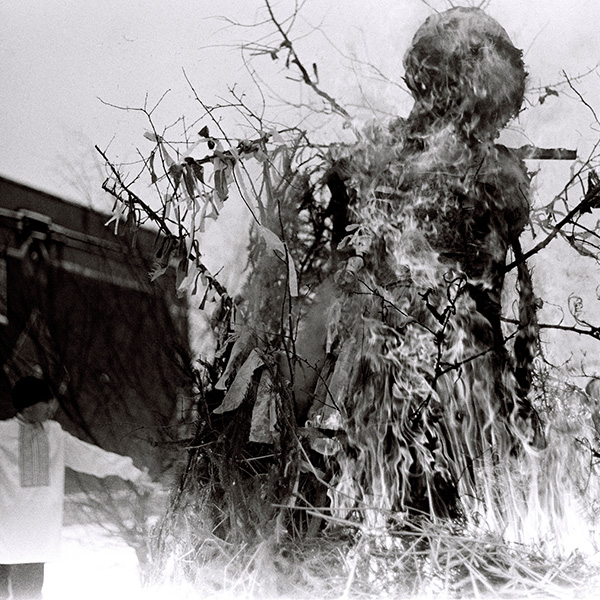

Sometimes at schools and folk hobby groups the brightest rites are reconstructed to achieve better knowledge of traditions, just as the amateurs of medieval culture reconstruct knight tournaments. Examples of such rites installed are: Shrove-tide together with ceremonial burning of man of straw or Christmas walk of the dressed up mummers group singing Christmas songs and wishing people rich harvest asking presents for it. It’s also possible to take a great interest in Midsummer romanticism by once visiting the festival in the city park or by going to the country for a corporative party. Midsummer is the shortest night of the year when people search for the fern-flower, jump over the fire, sing and dance in a ring, twine wreaths, and foretell the fate. Perhaps these are all the options for the city inhabitant of Belarus of today to get acquainted with folk holidays.

However in contrast to the knight culture, that remained in the past, folk or pagan traditions still exist in the villages. These traditions by some miracle survived seventy years of communist atheism that reorganized all the fields of people’s everyday life. Peasants continue bringing home birch twigs on Whitsunday, they do not send the herd to pasture before St. George’s Day, and do not eat apples before the Savior, or leave an unreaped sheaf in the field binding the ears in so called “beard”, they do not go to the forest and do not bathe during the “mermaid week”. One should at least once face with such peasant’s way of thinking, to which many unusual restrictions and rules are appeared to be important, to understand that the school material concerning our ancestry do not resemble folk tales any more.

Pagan belief survived all socio-political regimes and preserved the most important thing: special attention and respect for the nature. Any object banal at first glance such as a stone, a tree, a plant, a wreath, or a road appears to be endowed with symbolic meaning and animated: it brings luck, makes the transition to the afterlife easier, cures of a disease, protects form evil, gives beauty, bedevils, foretells the future. The nature demands obeisance because it’s the only way for harmonic and conflict-free existence for people inside the nature. People synchronize their lives with the natural cycle, surrounding the rites with liminal zones of this movement. And thereupon this very people’s separation from the nature due to definitive industrialization and urbanization reduces to zero the meaning of authentic folk traditions as well as the number of people keeping these traditions.

Setting out for a tour of Belarusian villages Andrei Liankievich decided to collect the evidences of pagan culture still existing in many corners of the country. Ten rites were included in the book (Marriage of the fireplace, Christmas rites, Summons of the spring, St.George’s Day, the Burial of the Arrow, Bush (Kust), Seeing-off the Mermaid, Midsummer (Kupalle), Dazhynki, Carrying the Candle) as well as the entire collection of sacred plants, animals and objects was presented. The project has distinct anthropological character which is reflected also in portrait specificity: frontal portraits with the figure’s central position in natural surroundings; this style is well known by classic works of Diane Arbus and August Sander. These portraits claim the presence of psychological, social and even physical existence of people. And all of this on the whole makes the world of pagan culture absolutely real for us.

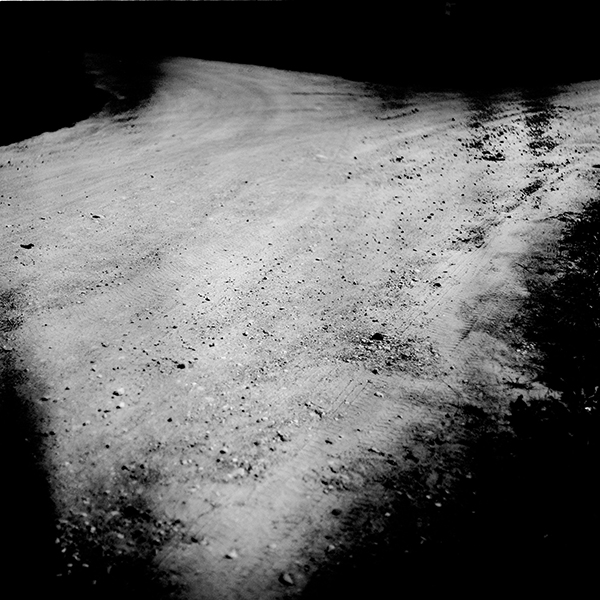

But at the same time the project does not just content itself with the compiling of encyclopedia of pagan’s material culture. We appear the witnesses of rites and senses not entirely clear for us, and therefore not entirely available. Thanks to the photographer’s efforts, pagan culture opens for us slightly, but hastily disappears. Peasants dressed in festive attires calmly make poses before a camera but in an instance leave the frame, disappear from the field of view, dissolve in the nature casting the last glance on the spectators, mysterious and inexplicable. Something happens to the stills themselves: they become spoiled by the light, darken, lose clarity, break suddenly, and transfer us from noisy festivals straight to a field or to the depths of a forest.

Andrei has succeeded in transmitting the pagan’s character itself: it can by simultaneously present and absent, noticeable and latent, evident and secret, literal and mystical. Folk dressing may attract us by its exoticism, but the close-ups of plants and animals make us think of something more than just exotic character of objects. Looking through picture by picture one gradually starts believing in the existence of the parallel world which covers with a thin layer our habitual surroundings. And now a birch is not just a tree but the symbol of womanhood, a baked pan-cake is not just food but the symbol of the sun, grass peeping out from under the snow is a constituent of a complicated rite.

Penetration into the folk tradition’s secrecy and creation of an unusual almost mystical image of the present-day Belarusian village distinguish Andrei’s project from everything done in Belarusian photography before him and from photography of Belarus in general. This is not just series of psychological portraits and not just a simple documentation of a way of life; this is a prudent and careful research of an entire cultural layer deliberately free from any politicization that has become nowadays typical of coverage of Belarusian topics. “I tried to answer the question who we were earlier and who we are at the moment being Belarusians”, says Andrei Liankievich. This question may address to themselves any readers opening that book. And perhaps entering the world of lost senses will help us to fill in the gaps in the understanding our own present.

Svetlana Poleschuk